Terror 21 Canada Trees

It is the 10th of April 2018. The depressing chase is still on to run down the mechanism for inbreeding depression and for outbreeding depression. In the last talk we were led to consider that possibility that in a very few years the birth rate for Sweden, and by extension the entire global productive middle class, would fall essentially to zero. This phenomenon had been suggested by history, archeology and plagues of wild mice and seen in laboratory mice. Prudence demands we look for the same thing elsewhere.

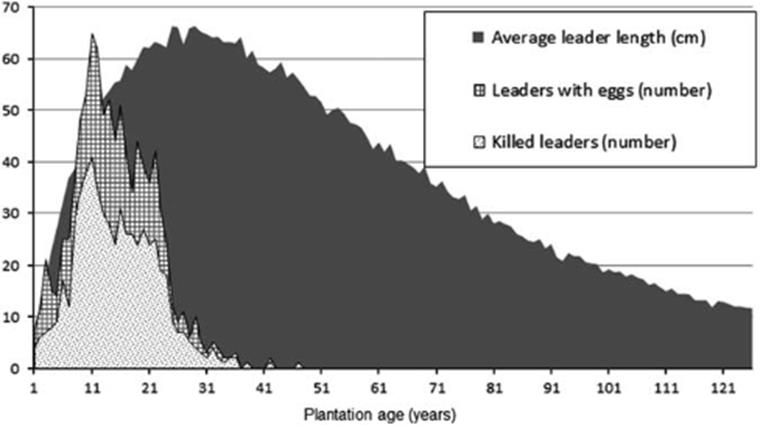

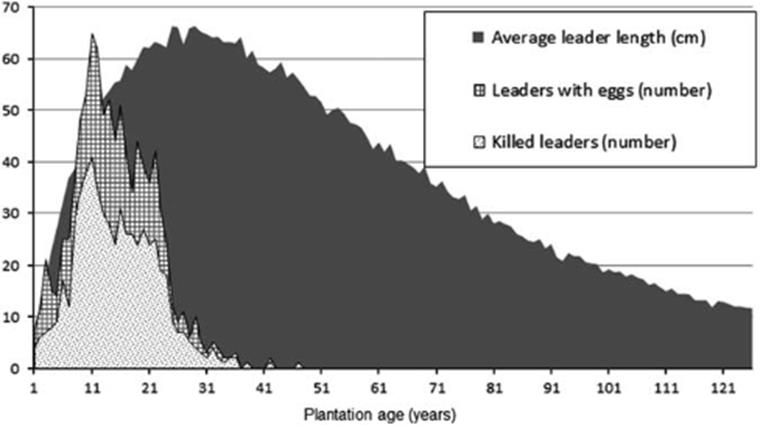

There have been studies of leaf cutting insects in Canada. The economic importance of such insects is obvious. What they have done has been to count the number of “leaders,” which means the shoots growing off the main stem of a tree, in infested trees that had insect eggs, the number of leaders that had been killed by the infestation and the average length of the leaders.

I should be happy to show you actual data, but what I have is a computer model they developed that gave a sort of idealized pattern. The horizontal axis is the age of the plantation being studied.

(14).

Detailed studies of the natural history of Pissodes strobi, and of the recovery and defect formation in its coastal host, Sitka spruce was used to develop a computer model, Spruce Results of the Spruce Weevil Attack (SWAT) simulation model showing the dynamics of weevil population, represented by the number of eggs laid on leaders and resulting damage (number of killed leaders) through the life of a Sitka spruce forest from plantation to harvest. In this model, weevil population is regulated by the availability of long leaders (a proxy for food supply), which are more prevalent during the juvenile stage of the stand. © 2015 Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by Natural Resources Canada Insects affecting regenerating conifers in Canada: natural history and management René I. Alfaro,1 Alvaro Fuentealba Can. Entomol. Vol. 00, 2015

As they report, the number of insects during the first fifteen years or so is regulated by the food supply, the number of long leaders, offered by the trees. However, after that, although long leaders remain plentiful, the numbers of insects drop. The population is then being regulated by Something Else, which I believe to be infertility that is a consequence of the large number of mating insects.

And just as we suspect in Sweden, the population rises swiftly, falls rapidly – the fast up and slower down pattern seen in my laboratory fruit flies and the computer model – seems to be leveling off a bit and then dies out. After about year 50 there are no more eggs nor dead leaders.

In isolation one might well conclude that the infested trees are able to produce some chemical that protects them. However, since the same pattern occurs elsewhere, in rich countries where food is plentiful and wholesome, the behavior of these insects strongly supports our suspicion that his will happen to humans in developed countries, with other countries coming along several years later.

The effort I made to predict the time course in humans could be wildly off – I don’t know about the future, having never been there – and I certainly hope so. Given enough time, we might be able to avert disaster.

In the next talk I shall turn to a happier note: the reproductive success of some black footed ferrets re-introduced in the wild.

YouTube video script directory

Home page